It is essential to ask photographers how they discovered the art of photography—a question deeply rooted in the tradition of mentorship within the photographic community. In the past, when information about the arts was scarce and costly, experienced photographers guided aspiring ones. Even today, this spirit of solidarity continues, ensuring the craft’s continuity and evolution.

The question, “Are there photographers who inspire your work, or how did you know you wanted to become a photographer?” offers insight into an artist’s roots in photography, revealing their personal journey and the reasons they felt compelled to capture the world through a lens. Over the years, the answers to this question have gradually evolved. Today, with a mix of joy and sadness, we recognize that photography has taken two distinct paths—50% of photographers are self-taught, while the other 50% have pursued formal education or mentorship, shaping their ideas, identity, and visual storytelling style.

How you learn the art of photography is not what’s in question—the true focus is on creating and contributing to the global visual culture. However, with Artificial Intelligence becoming a dominant force in creative spaces—especially with AI-generated photography taking center stage in 2024—the future of photography as an art form faces critical scrutiny. Its authenticity has long been measured through comparisons to the works of past and present scholars and enthusiasts, but as AI reshapes creative boundaries, the very definition of photographic originality is being challenged.

The Journal Project is about discovering an artist’s work and feeling a deep connection—one that sparks conversation and shared inspiration. Over the years, these conversations have woven together a community of like-minded photographers who follow each other’s journeys, engage with their work, and learn from discussions with artists who embody an authentic way of seeing.

During our recent gallery exhibition in Cape Town, we had the privilege of encountering photographer Jacques Weyers, whose creative portfolio immediately captivated us. His work held us in quiet fascination, compelling us to start a conversation about his chosen artistic approach—a little rebellious toward tradition, yet undeniably compelling. We explored his journey into photography, the motivations behind his medium, and the unique perspective that defines his work.

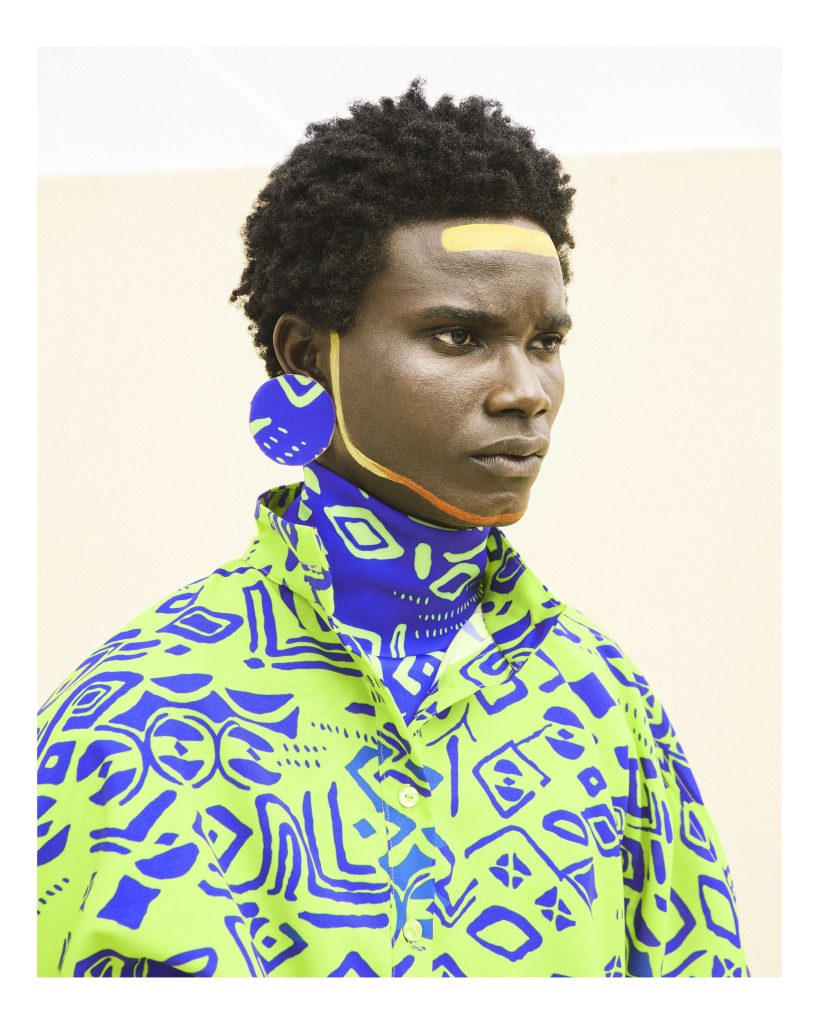

Colours can be very difficult to incorporate in our everyday life and sometimes, when not done either, colors become a block. But in your photography, it is evident that you’re well-versed in the art of colour theory. Please can you briefly explain your relationship with colours in photography. What do they mean to you?

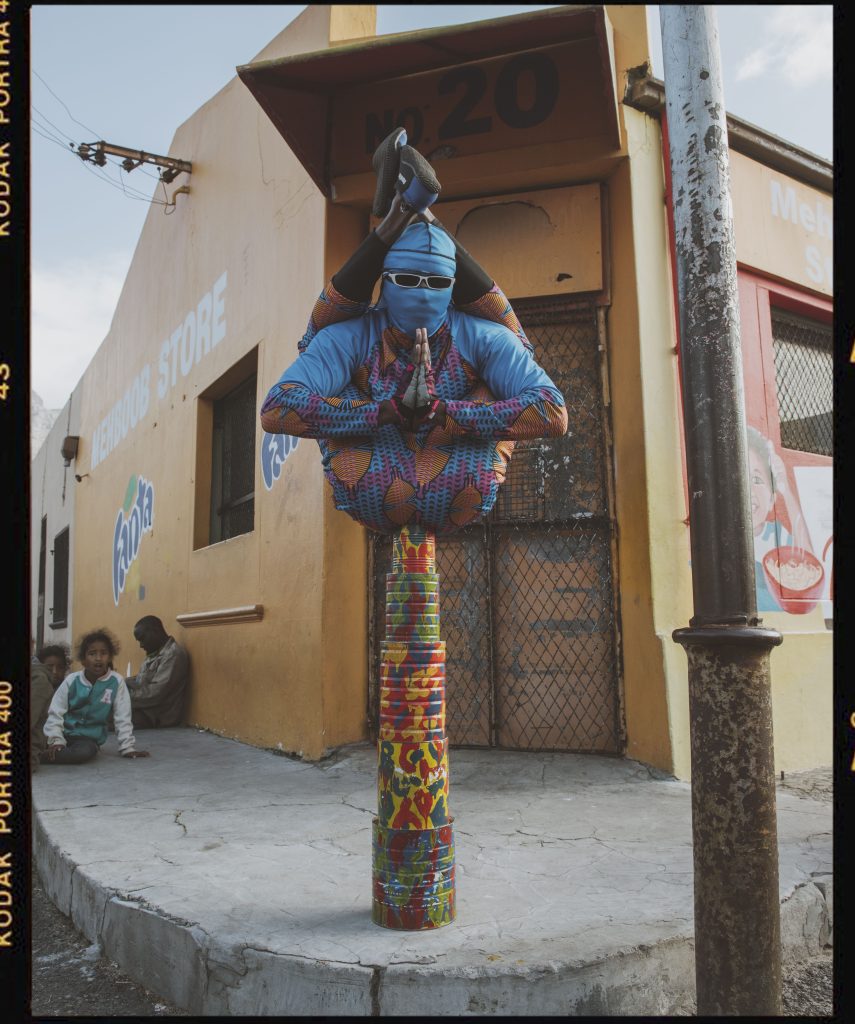

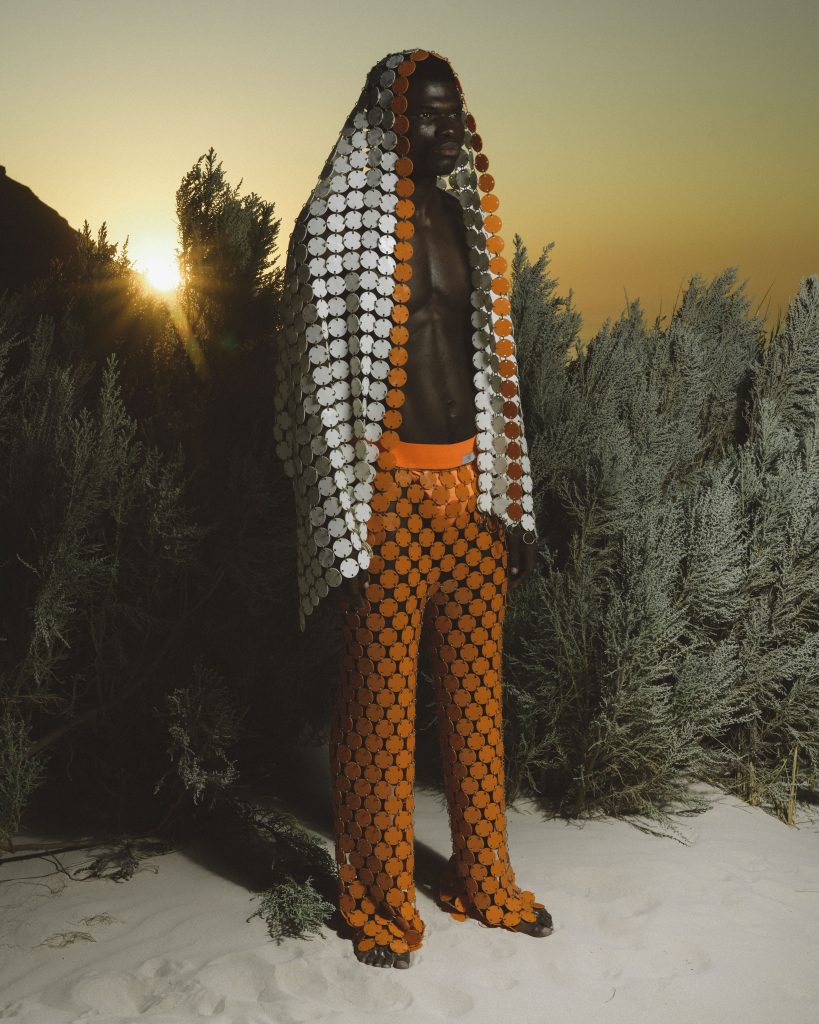

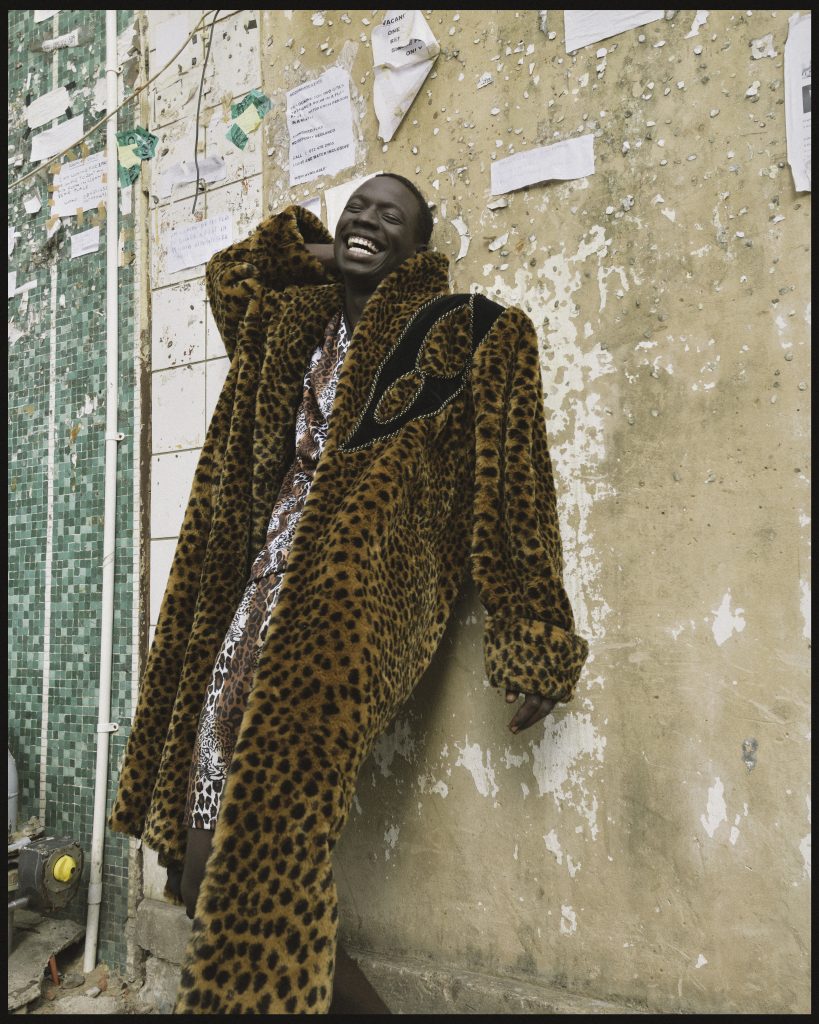

That’s actually a great question because, instinctively, my approach to any shoot I do revolves around some kind of colour inspiration. I’m always in search of some kind of narrative, and that usually starts with a location I come across somewhere in my daily journeys. I’m always on the lookout for somewhere interesting, something that has texture and colour and where I can tell a story. Once I find that place, whatever colour comes through will dictate the styling approach to the shoot. There is no real recipe, it’s whatever feels right to me. The more colourful and interesting the location, the easier I see and feel what I want to accomplish. If the location is a client’s choice, I try to find some kind of colour that relates to a colour in the garments. It helps me decide where I shoot what.

I am infatuated with the diversity of your work, including your models, fashion, make-up, and compositions. Everything seems present, which begs the question of how you chose to become a photographer and what inspired you to pick up the camera.

Thank you. I am blushing. To be honest, photography chose me. I studied graphic design and moved on to some art directing in a small ad agency, which led me down the photography route. Not being able to articulate exactly what I wanted to photographers, I picked up the camera and thought I’d better learn how to use a camera; otherwise, I was not going to get what I wanted in the images and from the photographers I was trying to direct. The camera just felt right, the process instinctual, and I got a lot of very positive responses from people who saw my photography. I took a step back, moved to London and started assisting photographers to learn what then was considered a trade, you didn’t just start shooting. Film was expensive, and the learning process took much longer. Developing a portfolio also took longer. Digital has made it much easier to be self-taught, and social media has made it easier to market yourself. In the beginning of my career, if you didn’t physically get a portfolio in front of a decision-maker, your work would never be seen.

Do you find your muses, or do they find you? Briefly explain the relationship between you and your favourite muse. How does that work?

I think it’s a bit of both actually. I like people who are interesting and have a uniqueness and don’t have to necessarily be models. I try to build a relationship before we even start shooting. I want the images to contain something authentic they love, whether it be their culture, where they are from, or anything that translates in the images that they can recognise in themselves. I can only find what that is by getting to know where they are from and who they are. It may not always be obvious to the people who see the images, but they will know. It just means more to me that it’s not just a fashion image but a piece of my subject as well. I’m also not trying to make them look physically beautiful; the beauty is in their authenticity. Africa is my muse before any model.

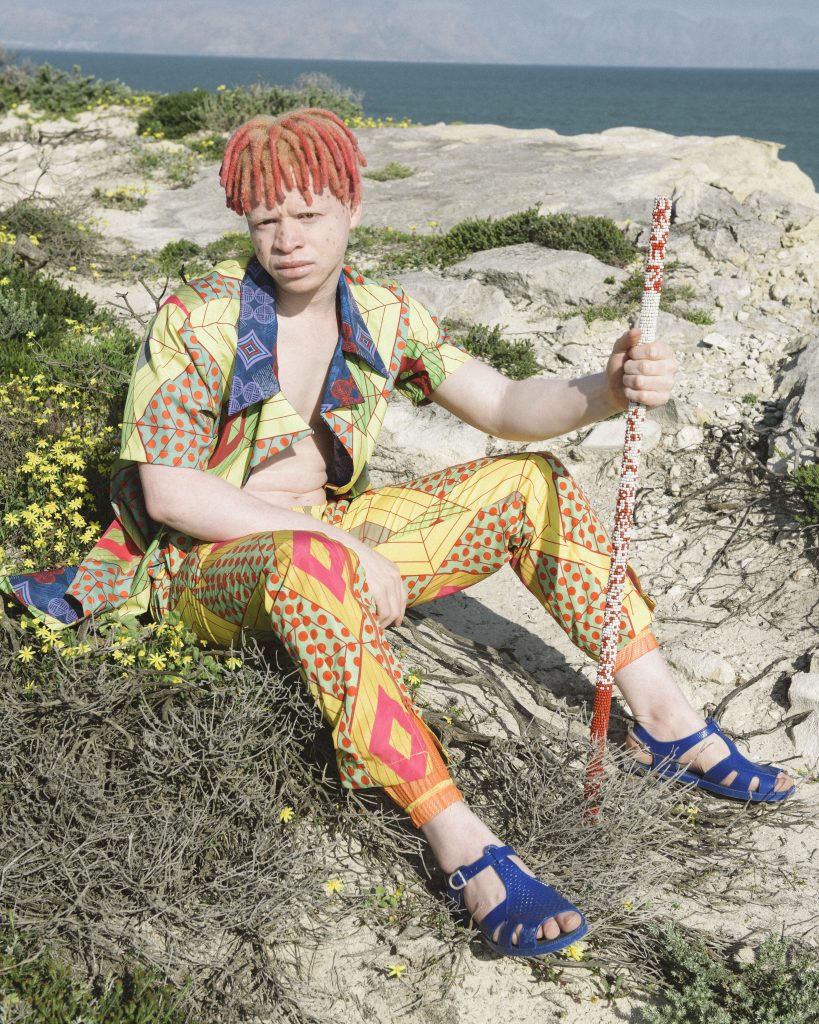

Which of the images you sent us is your favourite? Can you please briefly explain the story behind the image?

I would have to say the Image with the Albino girl and the guy with the white face paint. 2 parts to the story. Firstly, I was born and grew up in Umtata in the then Transkei, now the Eastern Cape, which is ancestrally Xhosa. When I was very small, my friends were black kids from the Pondolands who went through ritual initiations into manhood. They would have their faces painted white, called the Umkhwetha and go through ritual circumcisions to become a man. I discovered these guys busking at a traffic light in Durban with his face painted white, and it took me back to seeing the Umkhwetha passing through my rural home town of Umtata as a child. I knew I needed to use him in a shoot. Although not in the traditional way, it was just as inspiration for the story in my memory.

Secondly, I was in Durban for a shoot and had convinced my client to street cast to find someone different to the commercial models available in Durban. We cast for 3 days, and while doing digis of our selected cast for the final selection, this Albino girl came in to fetch her friend who was at the casting, not to be cast. She just had something in the way she stood and the way she moved. It took some convincing, but she finally agreed to allow me to take some pictures of her. My client and I were floored. She was incredible. We used her for one of our shoot days, but it was only weeks later, after seeing my white faced busker, that the idea of putting the two of them together for a personal project got realised.

Do you have a favourite camera to use?

I love my Mamiya RZ the most. The quality of the image that comes out on film is amazing. My favourite Digital camera is my Phase One IQ 180. The colour and total range are spectacular. It just has a cinematic colour range that’s unbeatable. It’s not a workhorse, though, so for my commercial work, I use my Fuji GFX 100. It has good colour rendition and is easy to use with hard work loads.

Given Cape Town’s dynamic blend of natural beauty, diverse cultures, and evolving fashion scene, how do you navigate the intersection of local identity and global fashion trends in your work, and what challenges or opportunities does this present in your creative vision?

Another fantastic question. I certainly wear two completely different hats when it come to navigating the local fashion landscape to international brands that come to shoot in South Africa and although local brands try encapsulate global fashion trends, Africa is a distinct trend of its own so I’m not really sure it translates in the local context and I think thats a good thing. I’ve argued for many years about why we are trying to African Americanise our Identity; we should be staying true to our own culture and heritage and remaining culturally African. Whether you are black or white, be African; this is where you were born and where you live. Embrace it and be proud of it. I know I am.

Are there photographers whose work inspires you to be more, or are you simply self-taught?

To be honest, I try not to look at other photographers’ work. Obviously, I have friends who are great photographers within the same agency, and we support each other, but I try not tot get influenced. Having assisted for 8 years, I learned more about what not to do than what to do. You have to shoot with your own instinct. I never wanted to be distracted by other photographers ‘ aesthetics. Technically, I learned a lot about lighting, but it never felt right trying to replicate their lighting it was a lot more rewarding figuring out how I wanted to light something. I learned about the psychology of a shoot and how to put that into practice, how to treat people and how to make clients trust me.