There’s something profoundly intimate, almost magical, about the moment a photographer stumbled upon photography for the first time. Most times it is unplanned, and often, it arrives quietly — through a borrowed camera from a friend, a casual assignment, or a fleeting opportunity that unexpectedly alters their path. For Rachel Seidu, her journey began in a religious setting, amidst the vibrant energy of a Church Community Festival. What started as an innocent curiosity about the media team’s “swag” turned into a thrilling lifetime photography discovery. That first rush of holding a camera, clicking the shutter, and capturing faces in a crowd sparked something indescribable — a mix of adrenaline, creativity, and a sense of belonging to a moment larger than Herself.

To be honest, the joy of discovering photography is the kind of joy that follows you home, makes you pick up a phone camera, and start documenting your world. Friends become subjects, everyday scenes turn into compositions, and simple images begin carrying deeper meaning. Over the years creating the Journal Project, taking a photographer on a quick trip back to the early days of discovery is often an enjoyable conversation, as we see most photographers reminisce about the imperfections — overexposed frames, blurry shots, watermarked experiments — because we know that it’s in those small, messy moments that a photographer’s voice starts to form.

Following the work of Rachel Seidu it is evident that the joy of photography hasn’t been just in getting it right, but in the act of trying, learning, and seeing the world anew through her lens. This is what makes Rachel discovery of photography so special. It’s pure, unfiltered enthusiasm, watching her talent unfold before her eyes, often with the encouragement of those around her.

In 2022, Seidu photographed the cover of the 2022 edition of We Need New Names, the Booker shortlisted novel by Zimbabwean author NoViolet Bulawayo. She was also shortlisted for the James Barnor and Yaa Asantewaa Prize in 2022. Selected group exhibition include Let’s take a moment (2022), O’da Gallery, Lagos, Nigeria, Sòrò Sókè (2022), Foto Wein, Young Contemporaries Exhibition (2020), Rele Gallery, Lagos, Nigeria and Boundaries of Reason(2021), Abuja Photo Festival, Abuja, Nigeria. Rachel Seidu is a member of Black Women Photographers and the African Photojournalism Database. She lives and works in Lagos.

Hey Rachel, I heard your main photography Instagram account was deleted — I’m really sorry to hear that. That must’ve been incredibly frustrating, especially with your whole catalogue of work on there. How are you feeling about it, and has it affected your workflow or visibility as a photographer?

My main Instagram deletion was a very bad moment for me because, I mean, I did not see it coming. I did not see it happening in a thousand years that I would lose my Instagram account because I don’t use it for anything else besides posting my work. So I never thought that could happen to me. Someone hacked my Facebook, turned it into a fraud account, and then Meta took down my Instagram account in retaliation. I still don’t think that’s fair because I appealed to them to let them know that I haven’t used this Facebook in like six years. And if you check, I believe you can see the logs and everything. You’ll be able to tell that I truly haven’t used it because I don’t remember the password. But I mean, I’ve accepted it now. I’ve accepted it and moved on from it because there’s nothing I can do about it. And I mean, I’m looking to the future and to see what the future holds for me. I still have my website, so there’s that. But it still hurts because I had work from when I started with my techno phone. I had work from those times there. So it’s incredibly frustrating, especially when you know there’s nothing you can do. But what can we do? We keep going. We keep moving. We keep pushing.

Also, We have always admired your work — how did you first get into photography? Was there a moment or influence that really drew you in, and how long have you been a photographer?

I got into photography in church, actually. I used to attend the Redeemed Christian Church of God. And in my local parish, there was this festival that was organized yearly called, I think, Festival of Moonlight. I honestly can’t remember right now. But yeah, that festival, teenagers are expected to volunteer for different departments. So I volunteered to join the media team because, you know, I love their swag was different and I wanted to be a part of that. They asked us to do a trial during church service one day and they gave us cameras, set it up and just told you where to click the shutter and then ask us to go into the crowd. It was very exciting for me and I loved the rush that I got from that. So I knew that I wanted to explore this more. And then on the day of the festival, they didn’t even give us cameras to eventually shoot. They gave it to the professionals. But just that singular thing already woke up something in me. And from then I started making pictures of my friends with my phone. So then I was using one Infinix device like that. So I started making pictures of my friends and then in December of that year, I think this festival thing happened in like October. In the December of that year, I rented a camera from a friend of mine, told him that, “oh, I’m a photographer now. Yeah, I was trained in church, you know.” So I gave him 2,000 or 1000 Naira and he gave me his camera. At first, I didn’t even know what to do with it because every photo I took was white. The exposure was crazy and I did not know anything about that camera. So I went to meet the local photographer in Opebi. I grew up in Opebi. I went to meet him and I asked him, “I don’t know if this camera is bad, like, can you check it for me? And he set it up for me.” Yeah, I still actually even have photos that I took from with that camera. If you want to see, I can show you some of them. But they are horribly watermarked with my name. Yeah, so that’s how I got into photography. And, you know, after that time, I just knew that, oh, I want to do this more. I want to do more of this. I want to take more pictures. And when I got into school, the very next year, I got into school in Uniben. And in my first semester, I tried to focus on my education instead. But in the second semester, I took photos of a friend after church. She said, “wow, you are very talented. You should be a photographer.” And then the hunger woke up again. I’ve been a photographer professionally for about five years now, yes. But if we count the other years that I’ve been using my phone to take pictures, it’s like seven, eight, I guess, yeah.

In the series of images you sent us, which is your favorite and what’s the story behind it?

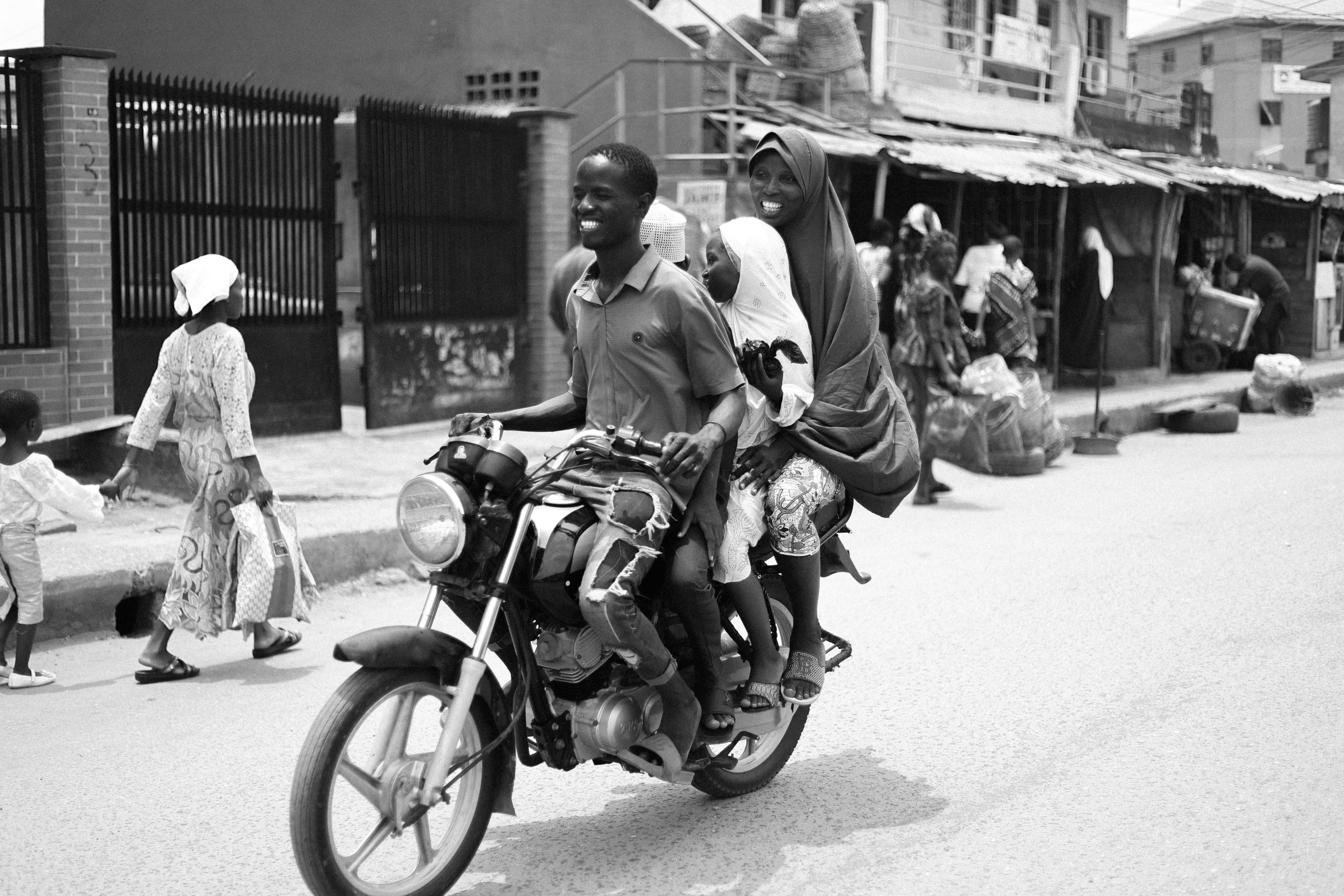

In the series of the images I sent, which is my favourite and what’s the story behind it? My favourite would actually be this image that you asked me to add from my Instagram because it came from a time when I used to make a lot of pictures of my younger ones. So all the kids in these photos, except one of them, are all related to me. Yes, all of them are related to me. So whenever I came back from school break, this was in 2020 actually, this happened in 2020, when I got back from school break, I was taking a lot of pictures of them because they were the only muses I had as at then. So I would just take them, let’s walk, let’s take pictures, and they were always excited for it. So this photo is my favourite because photographing these children is some of what helped me get my storytelling to what it was today. And the familiar relationship between them made it very easy. And from photographing them, I learned to photograph people as well. That’s why this would be my favourite photo from the selection I made.

In a country as culturally diverse and politically layered as Nigeria, how do you negotiate access to spaces and communities that are often guarded by tradition, bureaucracy, or mistrust—especially as a photojournalist whose presence might be seen as intrusive or exploitative? What strategies have you developed to gain genuine access without compromising your integrity or the authenticity of the story?

So how I gain access to spaces and communities is not by thrusting my camera in their face immediately. Yeah, I go there and present myself as a human first, talk to people, be friendly with people before the camera comes up. And even when that happens and they are not comfortable with it, I do not go ahead and take the pictures. One of the main reasons why I focus on portraiture in my work is because I like to have the consent and trust of the person I’m photographing. I like for them to be comfortable and that’s why sometimes I prefer portraiture as my mode. I’d rather do portraiture than take a random, I don’t know how to explain it, than just take a photo of them being unaware. I mean, yes, that’s good sometimes too, but I really love portraiture for that reason because they are comfortable enough with me and they let me photograph them. And how I make sure that I do not compromise the authenticity or integrity of the story is that I make sure that people are photographed with dignity no matter what position they are currently in life. I make sure that everybody I photograph, I photograph them how I would love to be photographed. I make sure that I see them and they feel seen in the photo as well. Yes, I make sure that every moment that is documented is genuine and not fake and that most importantly that the people are comfortable and know when to leave, know when they don’t want you to photograph them, know when they don’t want your camera in their face because yes, people should have the right to tell you no. Yes.

You’ve exhibited your photography multiple times, which is a huge accomplishment. How do you feel about the exhibition process as a whole—from selecting the images to seeing how audiences engage with them? And out of all your exhibitions, which one has been your favourite so far, and why?

I’ve exhibited a few times. How do I feel about the exhibition process as a whole from selecting to seeing how the audience engages with them? Honestly, exhibition times are always very anxious for me because I don’t really enjoy selecting photographs. I mean, if you did not send me this photo, I wouldn’t have remembered it because I have so many images and when it’s not a specific body of work it’s just really hard to select which and which you want people to see because you don’t know what the audience is even going to think about your work. You don’t know how even the organizers feel about the selection. So it’s a lot for me, but I’ve been lucky so far to work with people that know what they’re doing. I mean, not all of them to be fair, but quite a few, a good number rather, has made it easier for me by helping the selection and talking through everything. Of all my exhibitions, my favorite so far has to be the one in Doville last year, because I think it’s the first exhibition I’ve had that I was present, fully present from the selection to the picking what kind of settings I want the show to look like, like everything. I was involved in all of it. And being there and hearing people talk about how the work made them feel, it was also special. It was a special moment, like people walking up to me and telling me, oh, I loved your work. This is my favorite photo. This is why I loved it, you know, all of that was very special to me. And the title of the work is The Grass is Greener on the Other Side. It’s a work I collaborated with a friend of mine that wrote the narrative for it. It’s a dialogue between the Lagos Square community and the one in Doville, to see the similarities and the differences between both communities.

Have there been any photographers—Nigerian or international—who’ve really inspired your work, or would you say you’re mostly self-taught and guided by your own perspective? I’d love to know who’s shaped your vision, if anyone.

I mean, there are quite a number of photographers that have inspired my work: James Barnall, Gordon Parks, Vivian Mayer. Those are my absolutely favourite photographers ever in the world. I love their perspectives so much. I love the way they see the world. And those are the people that have mainly inspired my work. And sometimes I get inspired by photographers, their practices. But for my visual language, those are the people that have inspired me mostly. I would say I am mostly self-taught because I have never been to a photography workshop. But at the same time, there are so many people that have inspired me, not just with their works, but with their words as well. And some just mainly by their existence, their sharing of their work. That’s also inspired me. In modern photographers, like the current photographers right now, that I love their work, there’s, oh my God, what’s this lady’s name? Jesus. Please, I’m forgetting it right now, but she’s a French, Uruguayan photographer. And I really adore her work. Please, when I remember, I’m going to text it to you. I’m so sorry that I’ve forgotten her name right now.

Oh my God, also Seydou Keita, you know. And we share the same surname. I love his portrait work so much. Like, these are the people that their works have shaped my vision. And the way I photograph, when I started out photographing this way, being exposed to these people’s work early enough helped me, you know, decide the kind of photography I wanted to be. Yeah, and these are the people that have shaped my vision and my perspective. But when I photograph, I photograph out of how I feel.

Are you currently working on any photography projects that you’re excited about or that we should be looking out for? It’d be great to hear what’s next for you and what kind of stories you’re exploring right now

I’m currently working on a new project that I’m very excited… new project that I’m very excited for. It’s my own perspective on masculinity in Nigeria across queerness, cis heteronormativity, I don’t think I pronounced that well, and across homo, my brain is just skipping, what the hell? But yeah, it’s across sexuality, across religion, across life with different studies:

- The barbershop as a study.

- The football watching, you know, beer parlors where they watch football.

- Sports viewing centers, please, viewing centers as a study.

- Religion as a study, you know, across all of this.

And I’m very excited for it. I intend to make a book out of it next year, hopefully. But yeah, that’s all for the questions.