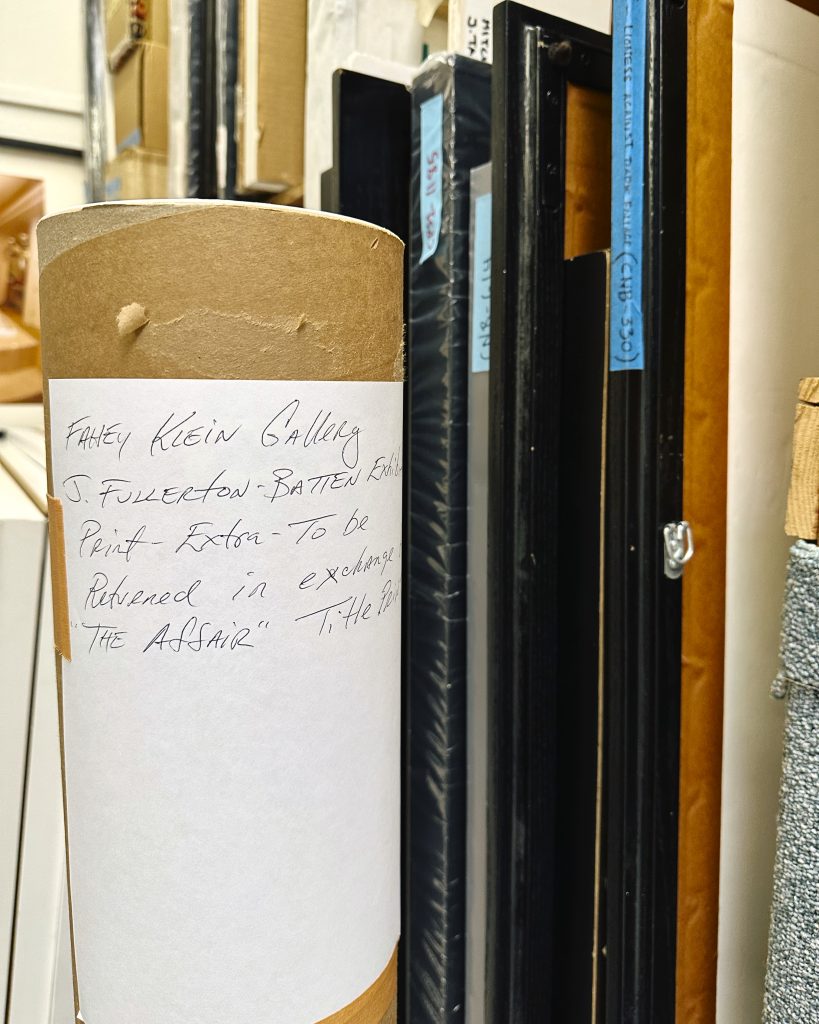

For nearly four decades, Fahey/Klein Gallery has been a cornerstone of photographic culture in Los Angeles, a space where the medium’s history and its most daring futures coexist. Founded in 1986, the gallery has championed both established image-makers and supported emerging voices, building a photo collection that bridges the 19th century’s earliest experiments and the visual languages shaping the present. Today, under the direction of Nicholas Fahey, the gallery continues to explore how photography navigates the world we live in today, as artworks, as visual evidence, and as a means of having more conversations.

As part of our ongoing dialogue with renowned photography collectors, Random Photo Journal spoke with Nicholas Fahey, director of Fahey/Klein Gallery.

Nicholas Fahey stands as a quiet yet decisive force in the world of photography. Although he directs one of Los Angeles’s most respected art spaces, the Fahey/Klein Gallery, he navigates the art world with a calm humility that keeps him just outside the glare of its spotlight. His presence is less about visibility and more about influence, felt through the relationships he builds with artists and peers rather than through overt self-promotion. In conversation, it is obvious that Fahey’s guiding ethos is one of stewardship. His devotion lies in serving the work, the artist, and the audience in equal measure, positioning him among contemporary photography’s most intellectually grounded custodians. As gallery director, his practice extends far beyond that of a conventional gallerist; he operates simultaneously as curator, collector, and mentor, roles that together form a philosophy rooted in a friendly vision rather than judgment.

According to Fahey, the gallery is not merely a venue for exhibition but an incubator for artistic evolution, a place where image-makers can sharpen their intuition, trace their creative lineage, and enter into meaningful dialogue with their audiences. His approach to collecting is both instinctive and informed: emotional in its immediacy yet shaped by years of inquiry across photography, filmmaking, and cultural entrepreneurship. Through his personal collection and his leadership at Fahey/Klein, Nicholas Fahey continues to articulate a living philosophy of engagement with images, one that values intellectually stimulating conversation over commerce, continuity over trend, and the shared evolution of photography as a vital, ever-expanding medium.

Fahey’s selections for the Collectors Project read like an exhibition, thoughtfully curated and thematically cohesive. Though not a physical exhibition. It is, rather, an intellectual one: a reflection of a collector’s cumulative emotional response to images encountered, felt, and engaged with over time, across the world. This catalogue brings together the works of twenty-three photographers. Among them are Steven Arnold’s Connecting to Infinite (1986); Tom Baril’s Calla Lilies (1995) and Calla Lily (1998), which together trace the evolution of Baril’s formal and tonal sensibility.

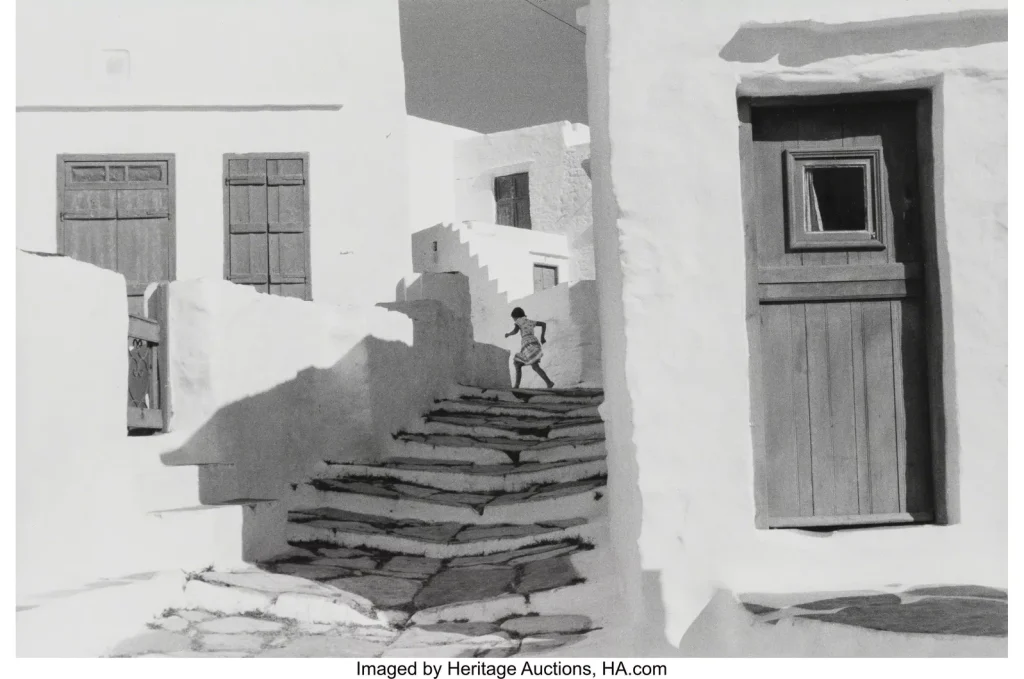

What an honour and privilege to come across ‘Siphnos, Greece’, made in 1961 by Henri Cartier-Bresson. That effortless, spontaneous photography with an observational quality that defines Random Photo Journal’s ethos: a seemingly casual moment captured with precision, yet resonant with narrative and emotion. Inviting reflection on sight, just like the other eclectic, thoughtfully selected images.

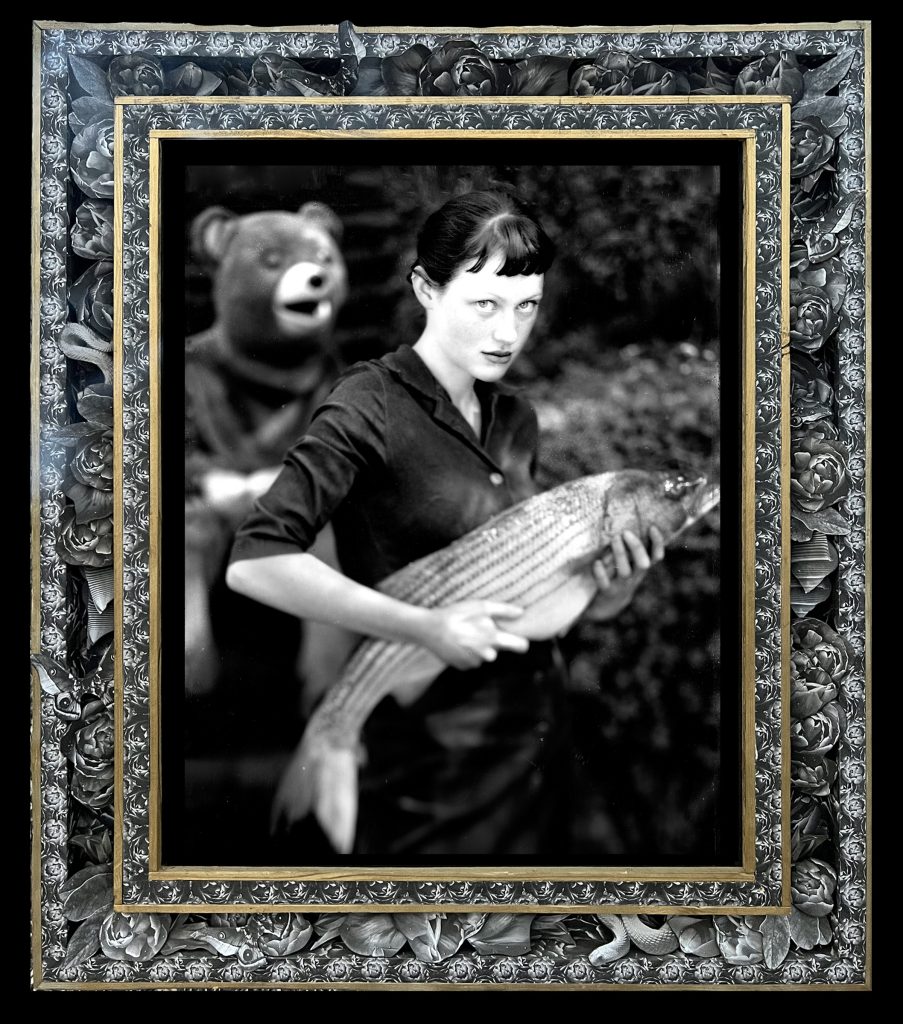

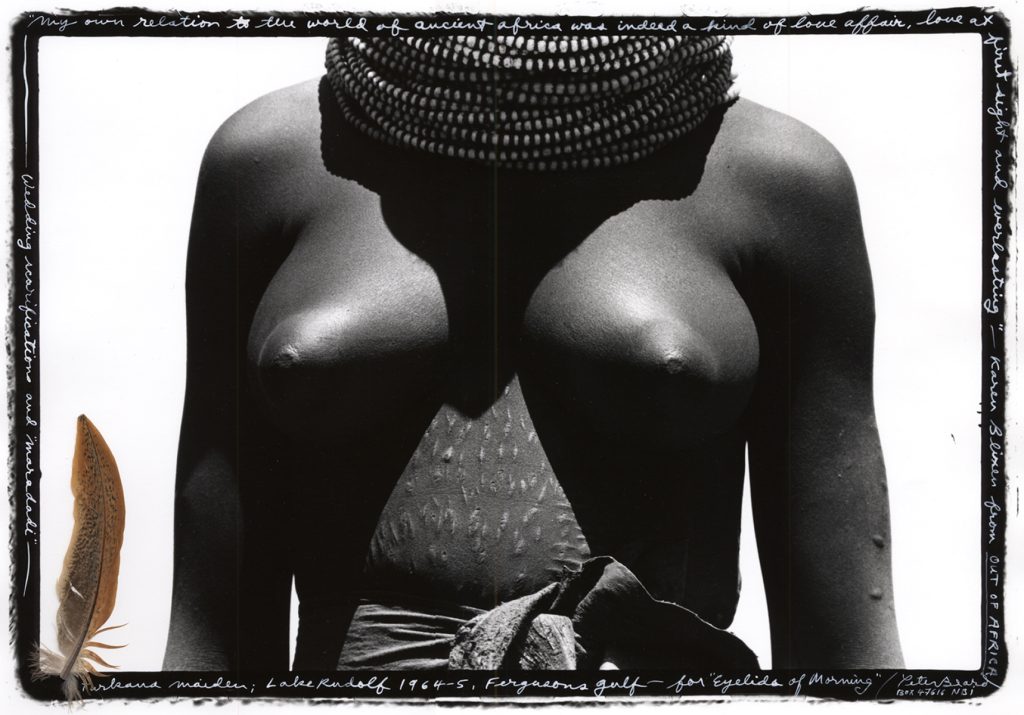

A clear affection for collage runs throughout Nicholas Fahey’s collection, most notably in the works of Peter Beard, Turkana Maiden, Lake Rudolph (1964–65), Janice Dickinson and Leni Riefenstahl, and Michael Garlington’s The Fishmonger’s Daughter (2000). These black-and-white prints, rendered on both toned and standard silver gelatin paper, possess a tactile materiality that reinforces the intimacy of their imagery.

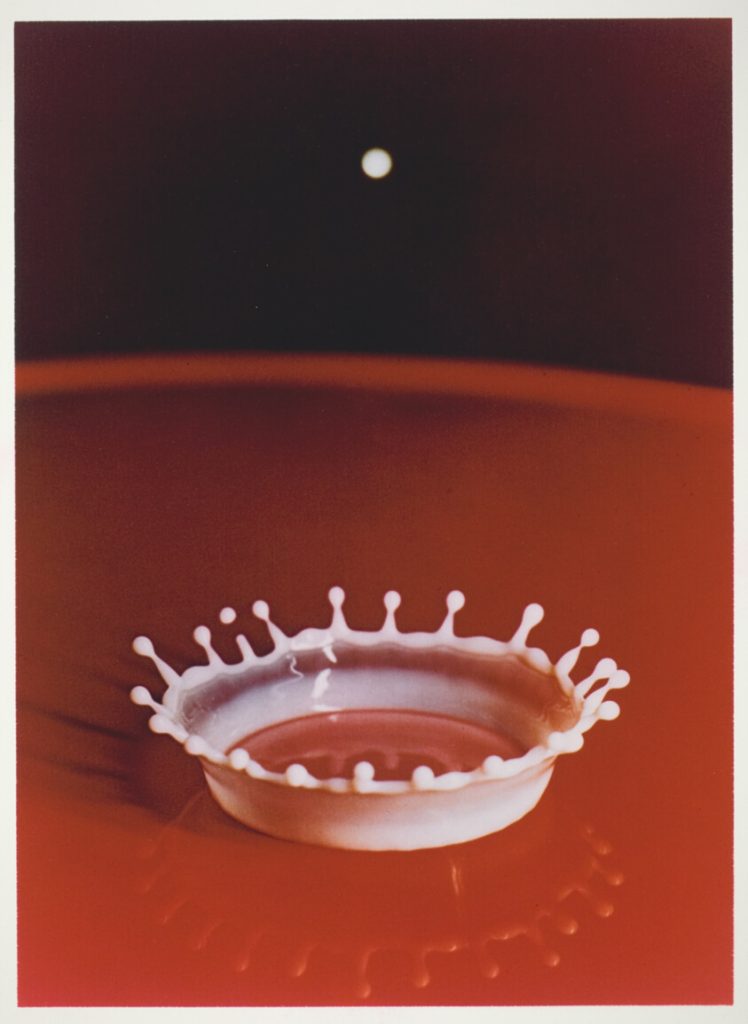

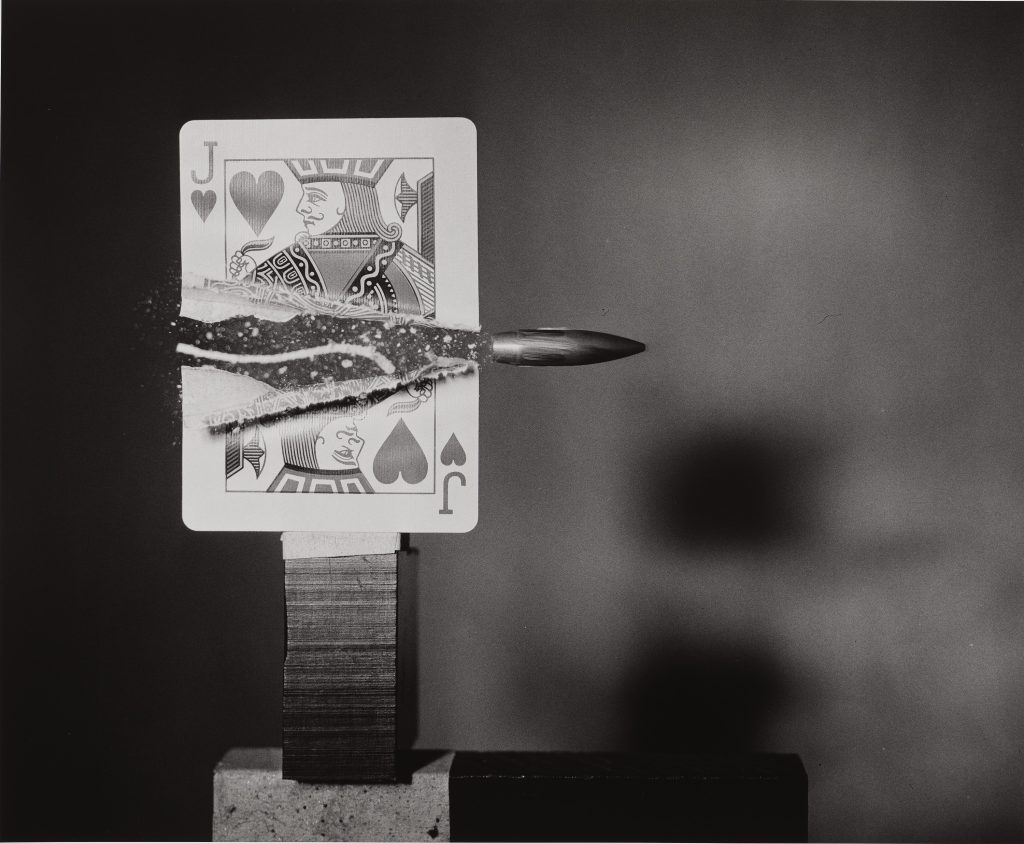

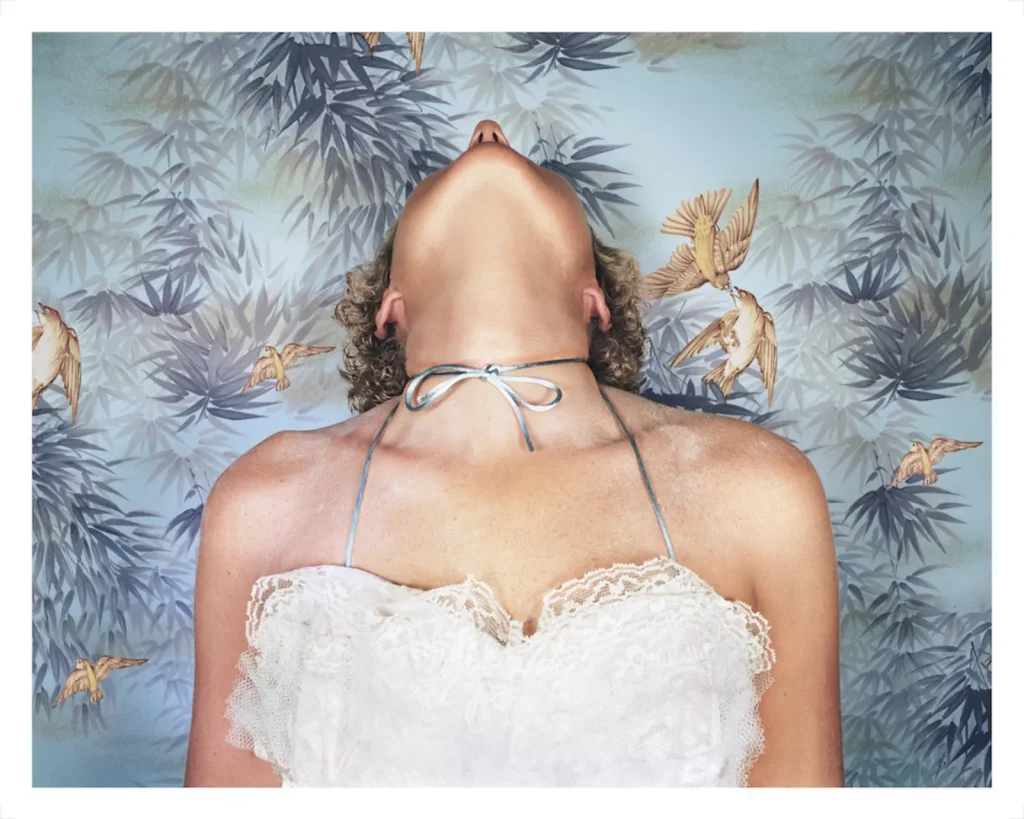

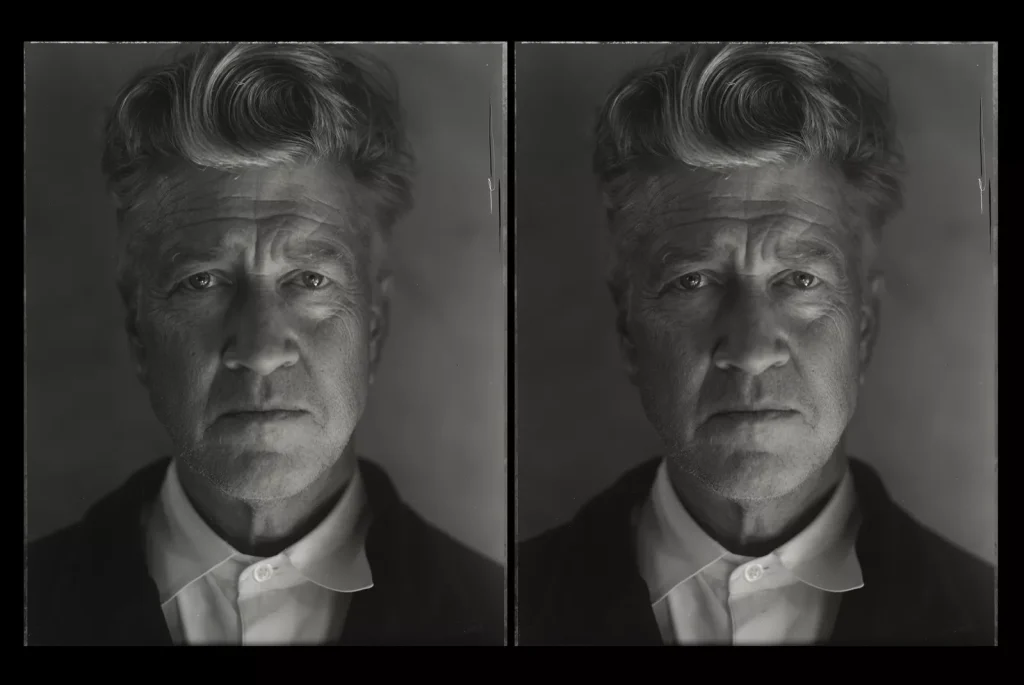

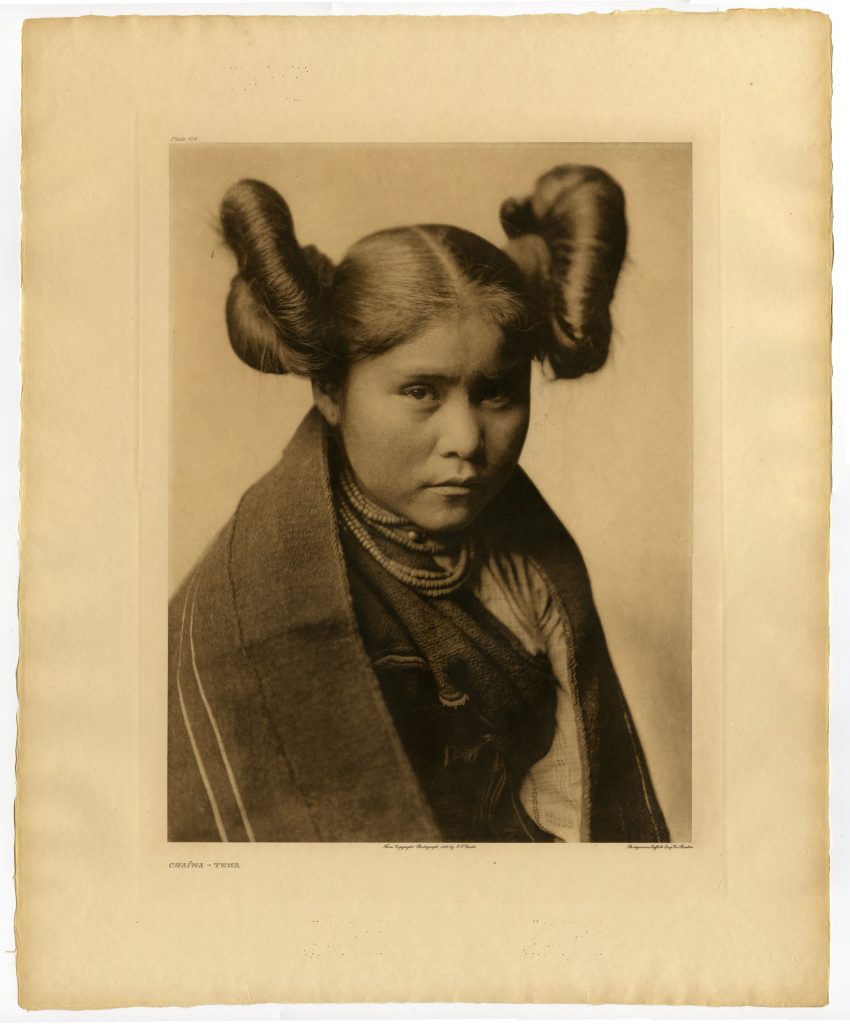

The ever-captivating Coronet Milk (1957) by Harold Edgerton anchors the catalogue’s selection of colour photography, followed by JoAnn Callis’s Woman with Blue Bow (1977), Edward S. Curtis’s Hopi Maiden-Hair (c. 1910), and Frank Ockenfels’s diptych David Lynch and DBB and the Mannequin, both printed as unique archival pigment works.

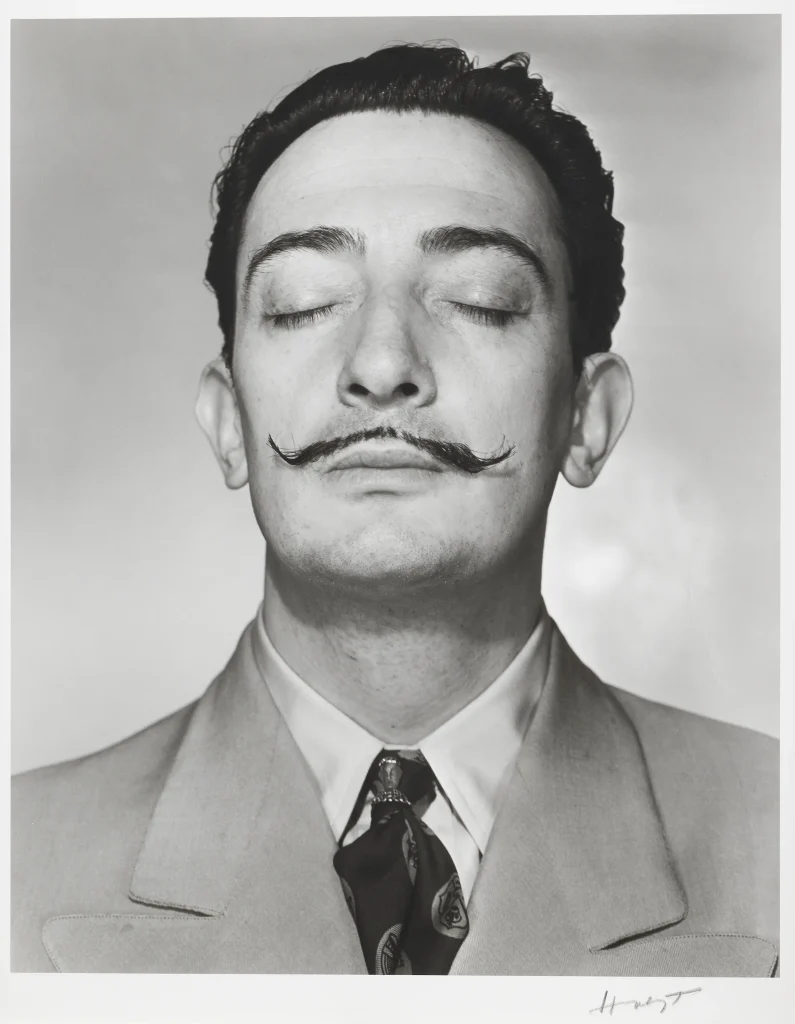

As Nicholas Fahey mentions in this interview, collecting these types of works requires both experience and a certain methodology; there is almost a science to it, he says. Age is also often considered an important factor in the market; the older the work, the more seasoned and archival it is deemed. In this regard, Horst P. Horst occupies a central place in the realm of seasoned photography, particularly archival and boudoir work. His Mainbocher Corset, Paris, 1939, followed by Lisa, V.O.G.U.E New York, 1940, printed on silver gelatin, exemplifies photography prized by long-time collectors. This catalogue also features Horst’s Round the Clock I-IV, NY and his portrait of Salvador Dalí, 1943.

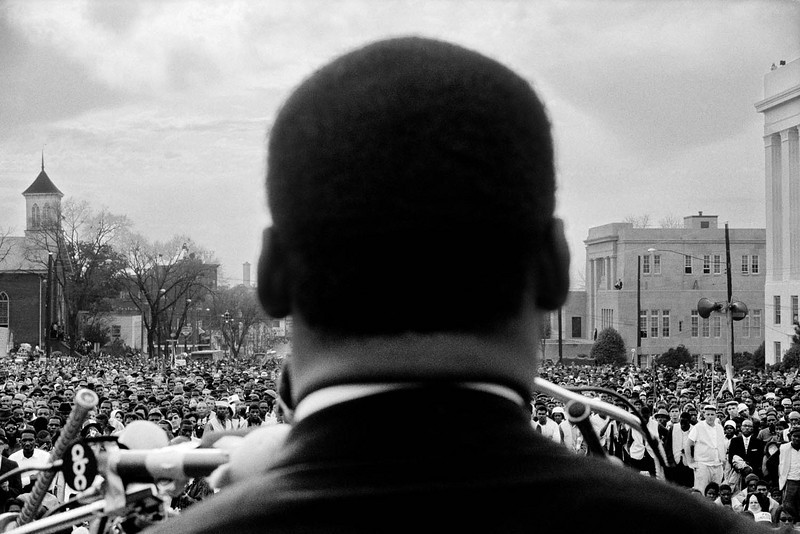

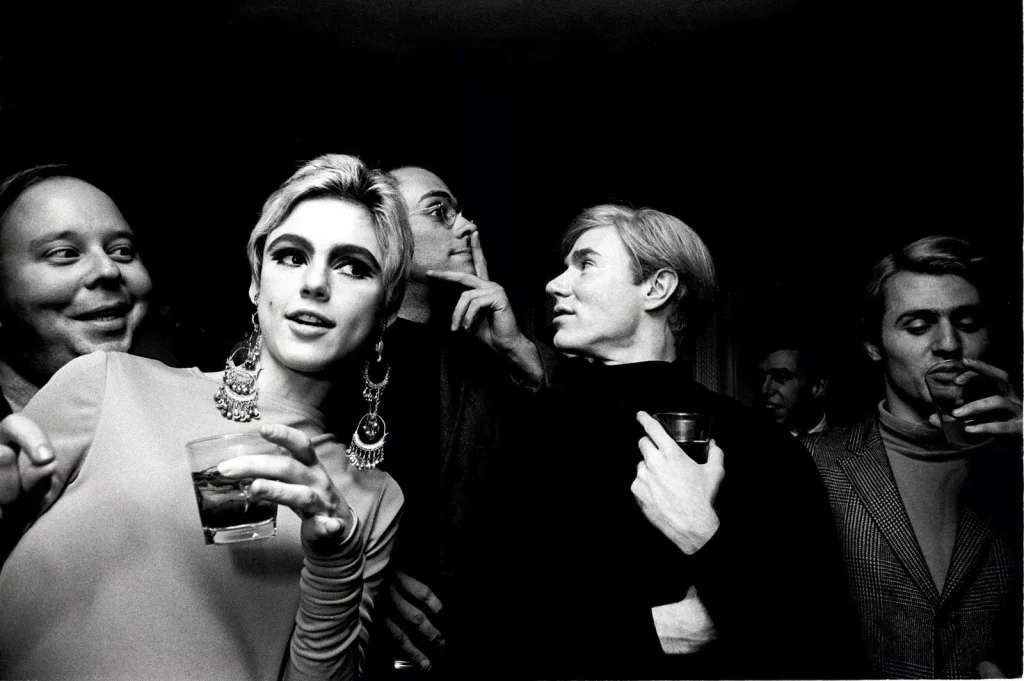

These images underscore that Fahey/Klein has consistently recognised and collected works that define excellence in their time. In the 1940s, boudoir photography held prominence, exemplified by Herb Ritts’ Consuelo, Pine Branch. The gallery also engaged with avant-garde subjects, from Christopher Makos’ Lady Warhol to Steve Shapiro’s Entourage, featuring Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick in New York. Norman Seeff, meanwhile, arrived in the late 1960s with iconic portraits like Patti with a Cigarette, capturing Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith, further demonstrating Fahey/Klein’s attunement to cultural and artistic currents.

So the first one is, what is the best medium to print for sale purposes?

Nicholas Fahey: Oh, wow. It comes down to the image. I don’t think that there’s one medium that makes sense. I would point out the exhibition that we have right now at Fahey/Klein. With Paul Outerbridge, I mean, those are carbon prints from 100 years ago, and they look glorious for what they are. And then you’ve got people like Paolo Roversi, who are still doing, you know, amazing C-prints, and also silver gelatin. I mean, I think it really comes down to the image, you know, for me. But, at the end of the day, if it’s black and white, I would love to see it as a silver gelatin print. And if it’s colour, I’d love to see it as a C-print.

How has being the custodian of these legendary photography works impacted the way you see photography, its future, and what works get to stand out?

Nicholas Fahey: That’s a great question. Well, for me, it all comes down to stewardship. It’s not my job to say if something’s good or say if something’s bad. It’s my job to help the artwork and the artist, find the audience that they’re talking to, so you know I really think about this place, Fahey/Klein, as an incubator for artists where I can, kind of, help them, you know, develop their practice, their business, and their audience and who they want to talk to and how to, because I think those are all really important, you know? When it comes to the photography community, and why people make images.

Should more photographers donate to galleries? And even if they wish to do that, does it still go through collector scrutiny regardless of their goodwill?

Nicholas Fahey: Don’t donate to galleries. Don’t give galleries anything for free. Because they should be… I mean, unless it’s part of a deal for them doing stuff for you. Donating to museums is a different scenario; artists should donate to museums. But it’s also important for the artist to understand who they are as an artist and what community they’re speaking to. And then donate to a museum… or an educational institution that has a scholarship around that medium or that practice, right? Because you want to donate your work, but you want to have it seen by people who understand what it is that you’re doing, institutions that are part of the conversation that you’re having. And I’d say that’s the same for going to galleries, where galleries that you want to work with and sell through, you’ve got to make sure that they sell to the people who are going to buy your shit.

What are some of the qualities a photograph is meant to possess to spark the need for collection, in your own opinion?

Nicholas Fahey: I say it all the time that humans have been communicating with images and symbols on walls longer than the languages we speak today. To be human is to be able to perceive art and have a chemical reaction inside your body or your brain that actually elicits emotion. So for me, it’s really, you know, it’s that animal brain where if it makes me react and it makes me feel and it… makes me stop and think and have an emotion. That’s important, and then it’s about identifying that emotion and understanding what in your past experiences has brought you to that emotion, and that’s part of just living a full life, and being human.

What unites all the works collected by Fahey/Klein? Is there a singular vision being repeated quietly in these works?

Nicholas Fahey: It’s a lot of people. It’s a lot of science. It’s a lot of experience. I also have a lot of stuff in my collection that, for one point or another, I would call a historical artefact of humanity and not just an artwork, but a record of a place and a time and of who we were as people or who we are as people. So, all the time I think about how it would be cool to have a collection that focuses on this or a collection which focuses on something else? But at the end of the day, it’s really about what I get excited about and also what my wife gets excited about because you know it’s not just my collection, it’s our collection, and so you know for me there’s also something important there, you know? Especially because our children are gonna have this collection. And just in the way that I identified parts of myself through seeing my parents’ collection, my kids are doing that. That’s really a fun part for me, certain things I’ll love, my wife will be like, not in a million years (Laughs). And, you know, all the time and vice versa, you know, she’ll be like, I love this. And I’ll be like, not in a million years (laughs heartily). So there’s something wonderful when you have a partner that you trust and enjoy art with to see where your Venn diagram crosses over.

In your own opinion, are collectors like yourself interested in seeing and collecting new works? I keep showing you all these new photographs, especially from the Journal we made, and I wanted to know if any of this new stuff impresses you.

Nicholas Fahey: Yes, it does. I always want to know that an artist understands where they sit in the history of image-making. If I’m talking to young artists and they’re making great images, but they don’t really understand the school of thought, or they’re reacting to someone else’s work, it doesn’t hit as much for me. And so, it’s really knowing that artists are trying to take a conversation that other people have been having and exploring and taking it to that next place. It’s like jazz, where it’s like, you’re just doing it, you’re feeling it, you’re going back and forth. And that’s what I really like to see. But also, you know, it goes back to that incubator aspect of Fahey/Klein as an incubator. And a lot of times it’s up to dealers and curators and people in institutions to help guide young emerging artists, to help them understand, because we’re in such a large visual library of images constantly. Things that you’re seeing in design or advertising or just in life are referencing art all the time. You might not understand what art it was referencing, and you might be referencing a commercial image. It’s always nice for me when I can help an artist see that the commercial image was brought about by this art or brought about by that art.

As someone who has been involved… I mean, based on our last conversation, you told me you are someone who’s been involved in a lot of ventures. What keeps you coming back to this gallery every day now?

Nicholas Fahey: It’s that entrepreneurial thing. It’s the stewardship of it. It’s knowing that I can be of service to people. I was very privileged and lucky to have the upbringing and experiences that I’ve had. And, you know, if I can just help people understand that it’s absolutely fulfilling and exciting. People used to ask me the question: They don’t anymore, but: Oh, do you take pictures too? Oh, do you, you know, you know, this whole thing. And I’m like, well, yeah, I did. I made music videos and shot films and photographed polar bears and made pictures for years, but I find it so much more fulfilling to help someone get what they’re trying to do and finish it. It’s so much fun to be a part of. Yeah. You know, it is like Random Photo Journal, you’re part of every single one of its issues. When I had my magazine back in like 2007, 2008, it’s like that thing where you’re like, yeah, to be a part of that and to help these people. It’s also always super important for me and exciting when I see somebody see something they like. For me, it’s always so fascinating to watch people walk through the gallery, people who don’t go to galleries and don’t go to museums and see what they’re gravitating towards. That’s constantly changing and constantly based on your perceptions of life and where you are and what you’re doing. Growing up in Los Angeles and living in Los Angeles, I’m a townie. I hang out with people I’ve known my whole life. And some of them have never been in the gallery. And they’re still very close friends of mine. But, you know, seeing how, trying to understand how those people see is, I think, sometimes just as rewarding as trying to understand how, you know, a curator at a major museum sees. They’re all seeing the same stuff; they just have a different language for how to describe it.

Random: Altadena was affected by the fire. Were any of your collections affected?

Nicholas Fahey: Yeah, my whole town burned down. When I came home, all of my neighbours’ houses were on fire. So, my neighbours and I put a perimeter of water hoses all along the fences and stopped the encroaching fire. Like, it came down here at one point. Like, this whole backyard was, like, 100-foot flames. And luckily, or not 100-foot, but, like, 60-foot. And luckily, I was sitting there, and I’ll show you this video. I filmed it. I was like, Cool! This is the end of my neighbourhood. Yeah. And all of a sudden, a helicopter came behind me and put the whole thing out. And all the neighbours ran in. It was wild. Yeah, it was wild.