Nostalgia has started to feel like an easy label, a word we reach for when we can’t name the tension inside an image. It’s as if every photograph must carry the weight of what was lost, or what we imagine might have been. But in reality, something is always slipping away, and something else is always arriving. That is the quiet truth in Tanya Traboulsi’s work: nolstagia is there, but we must move past it. Her photographs acknowledge that memory is porous, that presence and absence live in the same frame. The boys at the riverbank, the friends lingering near the water at dusk, the women and men who gather at the Beirut shoreline as if sunset were a shared ritual, none of them are performing the past. They exist in the immediacy of the moment, aware of the camera yet unburdened by it, as if the shutter might catch a small truth rather than an explanation. In this way, Traboulsi reminds us that photography doesn’t owe nostalgia to anyone; it only owes honesty to what stands before it. Tanya Traboulsi is a photographer whose work sits at the intersection of memory, identity and place. Born to an Austrian mother and a Lebanese father, and raised between both countries, she carries an in-between sensibility that shapes the way she sees the world. Her images often feel like fragments of recollection, composed with the quiet precision of someone who has learned to make sense of two lives at once. Traboulsi originally studied fashion design in Vienna before turning fully to photography, a shift that allowed her to translate her sensitivity to detail, texture and emotional atmosphere into a visual language of her own. Much of her work returns to Beirut, a city she photographs with tenderness and complexity. Whether she is wandering its streets, revisiting domestic interiors, or working with her own family archive, she approaches the city as both witness and participant. Her long-term projects, including Beirut Recurring Dream and her 2024 book A Sea Apart, explore how cities hold memory and how personal history can be mapped onto shifting landscapes. Her photographs have been exhibited widely in Europe and the Middle East, and she has become an important voice in the visual storytelling of contemporary Beirut. What defines Traboulsi’s photography is that she doesn’t rely on nostalgia; she builds a deeper emotional architecture around these moments. She captures not just what is visible, but the feelings that hover beneath it: longing, resilience, the fragile continuity of home. In her work, Beirut becomes a living archive of memory and contradiction, a place that holds its past and its possibilities in the same breath. Her images remind us that what we feel isn’t nostalgia at all, but something more complex, more human: the quiet recognition of everything we carry with us, and everything we must let go.

Your work often intertwines personal memory, identity and place, especially through series like Beirut, Recurring Dream or projects drawing on your family archive. How do you navigate the line between deeply intimate personal history and broader collective narrative when composing your images?

For me, the personal is always the gateway to the collective. I start from memory – my own, my family’s – but the moment an image exists in the world, it begins to resonate beyond me. In Beirut, Recurring Dream, I wasn’t trying to tell Beirut’s story, but rather to reveal how memory reshapes a city. The tension between what’s private and what belongs to everyone is where meaning often unfolds.

Coming from a bicultural and bi-racial background, Austrian and Lebanese, and having experienced childhood between those worlds, how has that “in-between” ness shaped not only what you photograph, but also how you see and frame a city like Beirut?

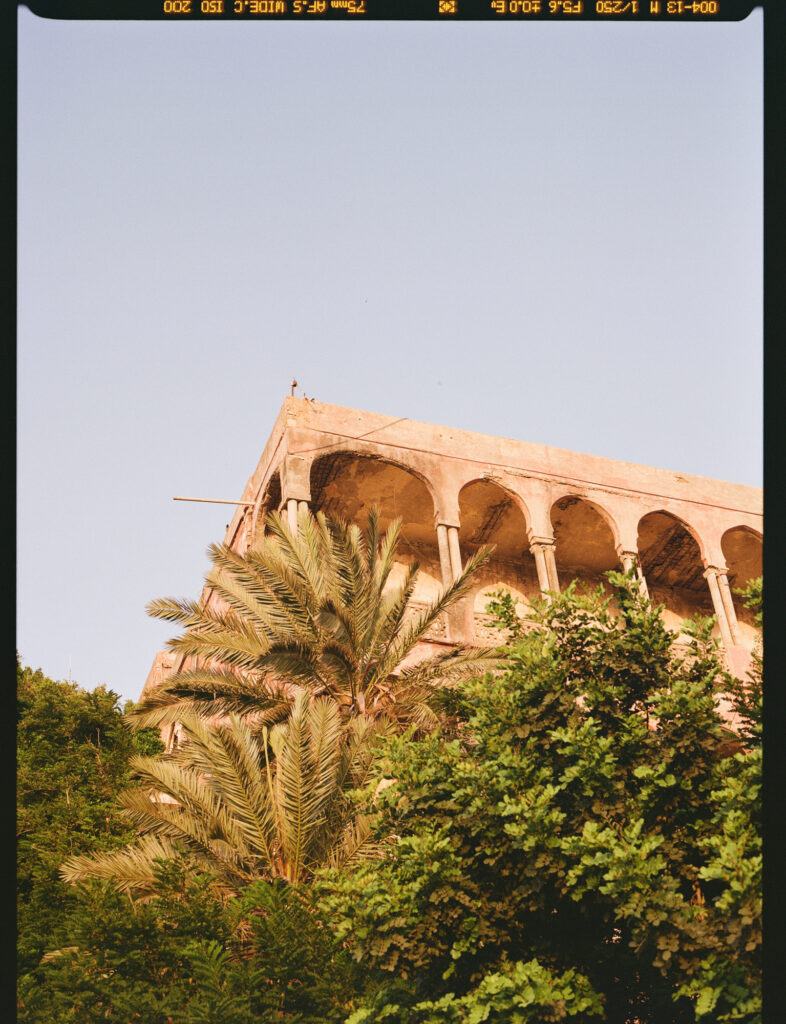

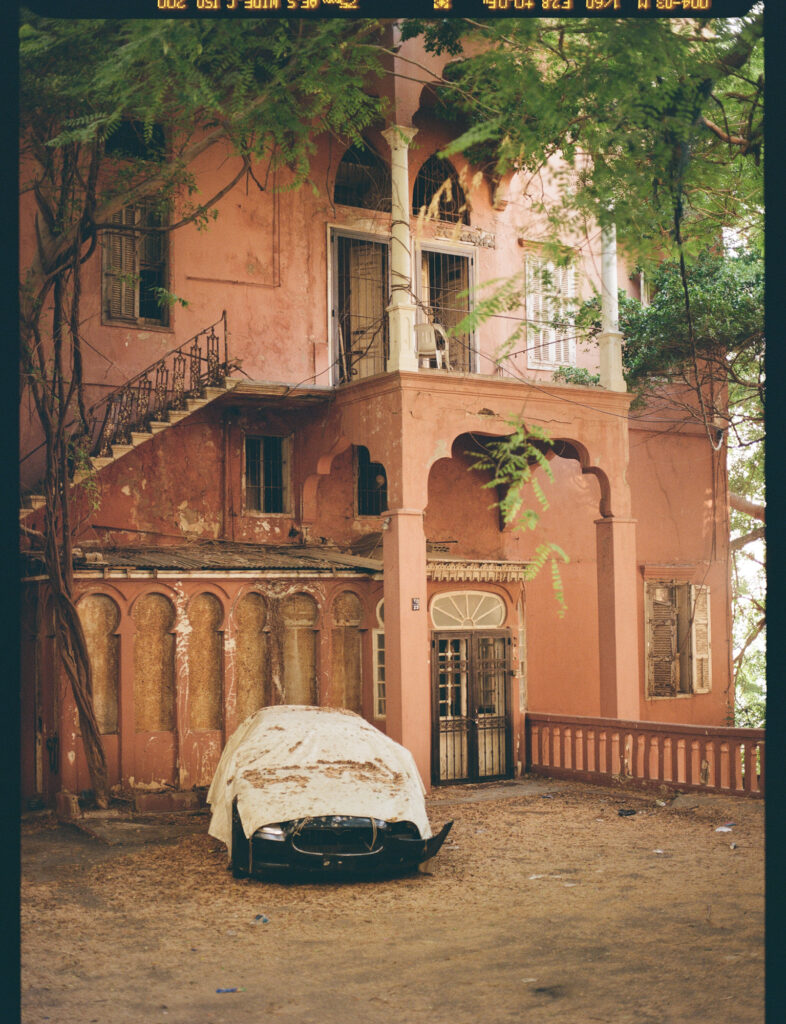

Growing up between Austria and Lebanon has shaped the way I look at everything. That sense of “in-betweenness” taught me to see with both distance and longing. Beirut, however, is home, it’s the place where I feel most myself, where I’ve lived my happiest and my saddest moments. When I photograph here, I move between presence and observation, between intimacy and reflection. I’m drawn to thresholds: sea and land, ruin and renewal, memory and now. This duality often finds form in how I work – through layers, reflections, and quiet fractures that hold different ways of seeing together in one

image.

Your most recent book, A Sea Apart (2024), presents a vision of Beirut as both remembered and reimagined. Could you walk us through how the book changed or refined your relationship to Beirut, and to photography, compared with earlier projects

What I loved most about A Sea Apart was how organic and intimate the process felt, working closely with my publisher, Chris at Out of Place Books. Together, we built the book slowly, intuitively, allowing it to take shape rather than forcing it into a fixed structure. That process taught me to let go of rigidity, both in photography and in editing. It reminded me that sequencing, like memory, can be fluid and instinctive. Through the book, I learned to trust what unfolds naturally, to embrace imperfection, and to see Beirut and my own practice – with a quieter kind of honesty.

In the series of images you sent to us, which is your favourite, and what is the story behind it?

This above image is very special to me. It captures that familiar view of the Beirut shore, the same one we see from the airplane window when returning home. There’s always a quiet emotion in that moment of descent, recognizing the city from above. But I’ve come to realize that I’m happiest on the ground, looking up at the plane instead – anchored, present, watching others arrive. It’s a simple scene, yet it

holds all the layers of departure, return, and belonging that run through my work.

In your creative process, you’ve spoken of working intuitively and letting images emerge without a rigid preconceived plan. Yet your work is also deeply structured, in terms of memory, archive, and the cities’ histories. How do you balance intuition and structure when you’re working on a long-term series?

For me, it’s necessary to be both flexible and disciplined. The work needs structure – a sense of rhythm and continuity – but it also needs space for intuition to move freely. I think of it as a dialogue between instinct and reflection. The archive, the memory, the history of a place – these elements give the work its framework. But within that, I always let intuition and passion lead the way. That balance keeps the process alive, allowing the work to evolve rather than simply be constructed.

How do you see the role of photography today in documenting cities, and are there other photographers whose work inspires you?

I believe it’s essential to document cities for future generations – to create an archive of the future. Beirut changes constantly, often abruptly, and when I look back at photographs I made in the 1990s, I’m always struck by what no longer exists and what has transformed. That visual record becomes a form of collective memory. I’m inspired by many photographers who are doing this work in their own contexts: Adam Rouhana, Tamara Abdul Hadi, Hannah Arafeh, Mohammed Nammoor, Chiara Wettmann, Hoda Afshar, Hussein Mardini, and so many others who are documenting life in their cities with clarity and urgency. Their images remind me of photography’s role not only as witness, but as a way of shaping how we understand the present once it becomes the past.

Finally, for younger photographers, especially those from diasporic or transnational backgrounds, or those who straddle different identities. what advice would you give about using photography as a tool for exploration, while still striving for universality and resonance beyond the personal?

I think the most important thing is to stay true to oneself. Look at others for inspiration, not competition; there’s room for many voices, especially from diasporic and transnational backgrounds. Don’t skip steps in the process; the slow work of learning, experimenting, and refining is what gives the images depth. And always stay open to exploring, to unlearning, to shifting perspective. When you work from a place of honesty and curiosity, the personal naturally expands into something that resonates beyond you.